-(8).png)

Original blog by The Commuter Club. This long read is brought to you by the Fleet Street Quarter.

Susie Boniface has been a journalist on national and local newspapers, broadsheet and tabloid, dailies and Sundays, since leaving school.

In 2009 she began blogging anonymously as Fleet Street Fox and published a novel, The Diaries of a Fleet Street Fox, after revealing her identity in the Times. In this piece for the Commuter Club, Susie takes us on a fascinating tour of Fleet Street through the centuries.

When I started writing anonymously about life as a tabloid newspaper reporter, I called it the Diaries of a Fleet Street Fox.

That’s because people all over the world know what this road stands for. They also have the same opinion of foxes as they do of journalists: scavengers, opportunists, vermin. Like Fleet Street itself, we’re glamorous from a distance, but mangey close-up. My marketing was free.

Today this road in EC4 is filled with coffee shops, lawyers, and bankers. The once-glorious edifices of newspaper giants are now used for something more profitable, like selling egg sandwiches.

But the River Fleet which flows beneath the street once ran black with ink and corpses. In the past, London was so foul that by the time the river reached the Thames, it was effectively a sewer.

In 1612, Ben Jonson took a boat trip along “this dire passage”, writing what is now considered “among the filthiest, most deliberately and insistently disgusting poems” in the English language.

During the Great Fire of London in 1666 people tried to put out the flames using buckets filled in the Fleet; it burned anyway. Considering the river’s contents, it may have been an accelerant.

After the fire, efforts were made to turn the Fleet into a Venetian-style canal. But in 1710, Jonathan Swift described it as still being filled with “sweepings from butchers stalls, dung, guts and blood; drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud”. It was bricked over for health and safety reasons.

Fleet Street was in what journalists call “a newsy patch”, an area where stories just happen. It was filled with the type of people your mother avoids but a reporter adores - hookers, prisoners, bankrupts, City of London merchants, the priests of St Paul’s, the barristers of the Inner Temple, and the hanging judges of the Old Bailey. An honourable mention must go to Mother Clap’s mollyhouse in Field Lane, a safe place for homosexuals to meet, at least until it was raided and Mother was put in the stocks.

So it was that on March 11, 1702, in a room next to the King’s Arms pub close to the ditchside that was then called Fleet Bridge, and is now the tarmacked intersection of Ludgate Circus, the world’s first daily newspaper was printed.

Well, sort of.

China and Korea invented moveable type 1,000 years ago, Germans created the printing press, and medieval newsletters were exchanged on trade routes across Europe. But that was for the rich. In Fleet Street, the business model was the only one focused on the hoi polloi. The earliest papers sold for about a penny, roughly the same price as a loaf of bread, and those two things are still worth about the same today.

Roughly half the population were literate, but mass-produced, cheap reading material is likely to have helped many learn to read. You can imagine a group of people clubbing together to buy a scandal rag, gathering around to hear someone read it, perhaps picking out their first words. It gave power to the powerless.

Publishing had been taking place in this area since around 1500 when Wynkyn de Worde set up shop in Shoe Lane. He produced romances, poetry, guides on animal husbandry, and ran the first book stall in St Paul’s churchyard.

But printing things so anyone could read them was socially unacceptable. Those early copies of plays, legal papers, and song sheets could all be incendiary, defamatory, and/or political.

The Tudor monarchs decided printing must be licensed. They gave the Star Chamber of privy counsellors and judges the power to inflict any punishment short of death on rule-breakers.

It gave the monopoly on printing to the Stationers’ Company, which in return for having the lucrative copyright on approved works - such as Shakespeare’s plays - was tasked with smashing presses producing unapproved ones.

Fleet Street is lined with medieval alleyways called courts. Legend has it that when the Stationers’ men were waiting outside to pounce on illegally-printed material, bundles of waste paper would be sent out the front, while the real stuff was rushed out the back. Material the government didn’t want anyone to read was on the streets before they could stop it, a bit like sending a tweet.

Officials eventually realised they couldn’t stop the press. Instead, they decided to abuse it.

By the end of the English civil war, printing was used for propaganda, and in 1645 in a move that upset future historians, both sides declared victory at the Battle of Naseby.

Afterwards the Roundheads, who had actually won, seized Charles I’s baggage, uncovered evidence of his intent to bring Catholic mercenaries into the war, and published it in a pamphlet which the Piers Morgan of his day might well claim to have ended the conflict with. The Cavaliers never recovered, Charles surrendered within a year, and his reign and body were shortened considerably.

Charles II restored censorship and by 1665 the only licensed ‘newspaper’ was the London Gazette, which is still the official journal of government business, and still less interesting than the paper it is printed on. This is the yawninducing intro on its front page splash on the Great Fire of London:

“The ordinary course of this paper having been interrupted by a sad and lamentable accident of Fire lately hapned in the City: it hath been thought fit for satisfying the minds of so many of His Majesties’ good Subjects who must needs be concerned for the Issue of so great an accident, to give this short, but true Accompt of it.”

The ink was now out of the pen. Censorship became impossible, and printing blossomed. The rich fell back on the laws of defamation to protect themselves, and pamphleting gained in popularity. In 1701, Daniel Defoe used one to demand the release of political prisoners - the first journalistic campaign for justice.

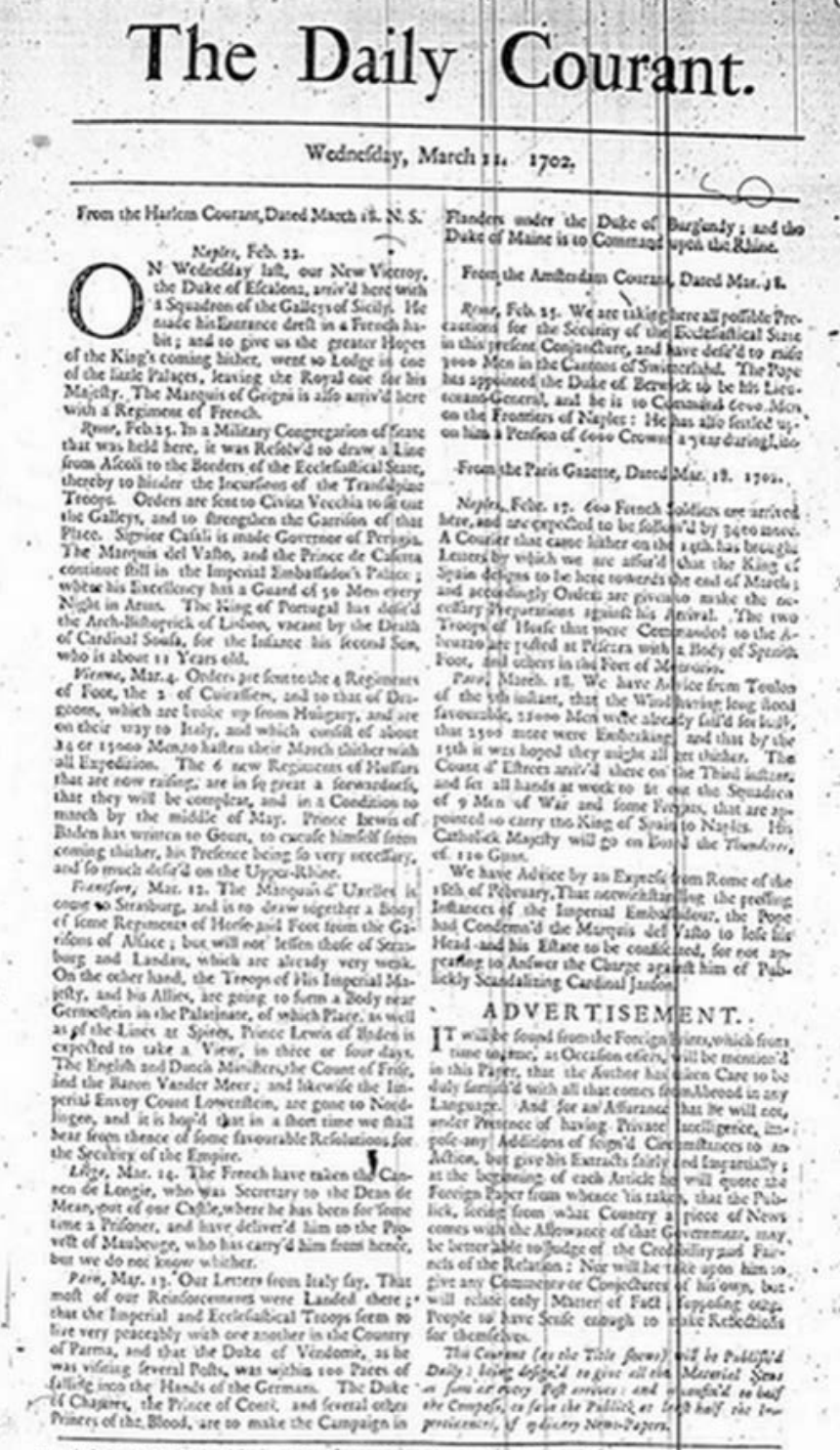

But what happened in 1702 was the first time something recognisable as a daily newspaper was printed. The Daily Courant consisted of a single page of news from around the world, with adverts on the back. Its aim was to cover events impartially, with sources clearly stated.

This is the first-ever editor’s letter, and clause 1 of the industry code of conduct which guides journalists today says much the same.

The Courant is thought to have been published by a woman called Elizabeth Mallet. If Fleet Street is institutionally sexist, it is despite the fact the first newspaper baron was a baroness. As she sold the paper 40 days after it was founded, she was also the first to decide that journalism had no future.

She was wrong. Since then Fleet Street has become the longest road in the world, stretching from Tunbridge Wells to Timbuktu. Newspapers, TV stations, and news websites everywhere still use the Daily Courant’s model, campaign for their readers, and are an embuggerance to governments.

This part of the world has a long history of people fighting authority. At the Fleet bridge up near what is now known as King’s Cross, Boudicca battled the Romans. Outside Temple Bar, Defoe was ordered to stand in the stocks for the crime of seditious libel after poking fun at politicians. The crowds drank his health, laid flowers at his feet, and bought thousands of copies of his work, because publishers know a sales opportunity when they see one.

And in 2013, when Margaret Thatcher’s funeral cortege travelled along the street which, with Rupert Murdoch, she had done so much to change, some of the good people gathered in Fleet Street applauded, while others turned their backs.

I wonder how many of them were among the 6,000 inkies, or printers, and connected trades sacked without warning in 1986. Overnight, Murdoch moved the rest of his editorial staff from Bouverie Street and Grays Inn Road to Fortress Wapping, where shiny new computers could do their jobs more cheaply, and never went on strike.

In the wake of that bitter industrial dispute, every other newspaper packed up and left. They digitised, modernised, and improved.

Fleet Street was no longer just one postcode. Its diaspora grew into a multimedia, multi-billion pound industry.

What they left behind had to change, too. Fleet Street’s publicans lost customers with the most reliable thirsts in the world.

The days used to go like this. When the editor called morning conference, hacks would go to the pub for a heartstarter. They might have a morning snooze in the press bench of a quiet courtroom, then a liquid lunch with a contact, before retiring to the pub again at about 3pm for a proper drink, and write their copy.

They would then celebrate their exclusives or drown their sorrows until the pubs closed, and when they staggered into the newsroom next morning to face the tyranny of an empty paper, they needed a drink to deal with it.

That atmosphere has changed, but not been erased. There are still older subs who swear it is impossible to write a good headline without a drink to loosen up, and whether a hack has been arrested, freed, or killed, the traditional spot to mark it is the pub.

But where you drank was a matter of territory.

You should only meet other journalists in the Old Bell, the boozer for those who’ve just been hatched, matched or dispatched at St Bride’s, the journalist’s church which is the only place of worship where the priest doesn’t seem to mind that the flock consists of entirely unrepentant sinners.

Journalists from papers other than the Daily Mail would wander into the Mucky Duck, or White Swan, in Fetter Lane at their own risk, the Telegraph claimed the King and Keys next door to the office for their own, and the Mirror when it was based at Holborn Circus always drank in the White Hart, more fondly known as the Stab in the Back.

It had its own apartheid - inkies in the saloon, journos in the lounge bar.

The landlords of Fleet Street didn’t just sell booze. Hacks also needed telephones, pens, painkillers and excuses, and were prepared to put all of them on expenses. Newsdesks seeking missing staff would ring around the watering holes to find them. At the Stab there was a sliding scale of charges for barmen to say “I haven’t seen him” to whoever was asking - £1 for the newsdesk, and £2 for wives.

The Mirror building, complete with Robert Maxwell’s helipad on the roof from which he used to urinate over the side onto passers-by, was knocked down, and the HQ of Sainsbury’s now occupies the site. The Stab was sold, and became a Pizza Express.

Some of these places remain: the Express building, known as the Black Lubyanka, and Peterborough Court where the Telegraph resided. These offices had basements sunk deeper than the Fleet itself, to hold the massive presses that thundered through the night and made the whole street shake.

Despite reports of our demise, Fleet Street has more customers, today, than at any point in human history. There are 3.5bn newspaper readers worldwide, that’s half of all humans on the planet, with even more online.

But advertisers and readers don’t value us any more now than they did when we were fish and chip wrappers - you cannot hold a webpage in your hand. And what Fleet Street has achieved in the past 319 years is equally hard to grasp.

The trade which began here was so infectious that most humans on the planet expect their governments to be accountable, for speech to be free, and for those in wealth and power to be exposed if they do wrong.

The dissemination of information to everyone who seeks it and plenty who don’t means that those reading these words have literate, socially and politically engaged staff, or co-workers. It’s why some became entrepreneurs. It’s how people decide who to vote for. It has made our country and our world what it is.

Today the Fleet is London’s biggest underground river, and is officially a sewer. Journalism is still considered the most terrifying thing ever to crawl out of a disease-ridden slum. The rich still think we’re vermin, which is all the proof you need that Fleet Street is still strutting its stuff.

If you went back in history and told all this to Elizabeth Mallet, she would never have sold. And if you told Charles II, he wouldn’t bother with censorship. He’d get himself a website, and a paywall.

From Mother Clap to Lord Rothermere, the river of ink which ran through this bit of town was an essential part of your evolution as a species. There is no museum about what the people who lived and worked in Fleet Street have achieved. Despite being home, then and now, to highly-skilled tradespeople, this is still an unloved, under-appreciated part of the world.

But it is the things you find in dustbins, as any fox will confirm, that define what you are.

Find out more about Susie and her work at www.susieboniface.com.

Original blog by The Commuter Club. Brighten your journey with an exclusive selection of podcasts, playlists and stories, curated especially for Londoners. The Commuter Club will transport you from your train carriage to a rooftop bar in the City; from your seat on the bus to tranquil garden squares; from the Northern Line to the kitchen of a Michelin-star restaurant. Be the first to read and listen to stories from the streets of London by signing up to their mailing list. Plus, get access to exclusive offers just for commuters! Sign up here.